Los Alamos: Beginning of an Era 1943-1945

New World

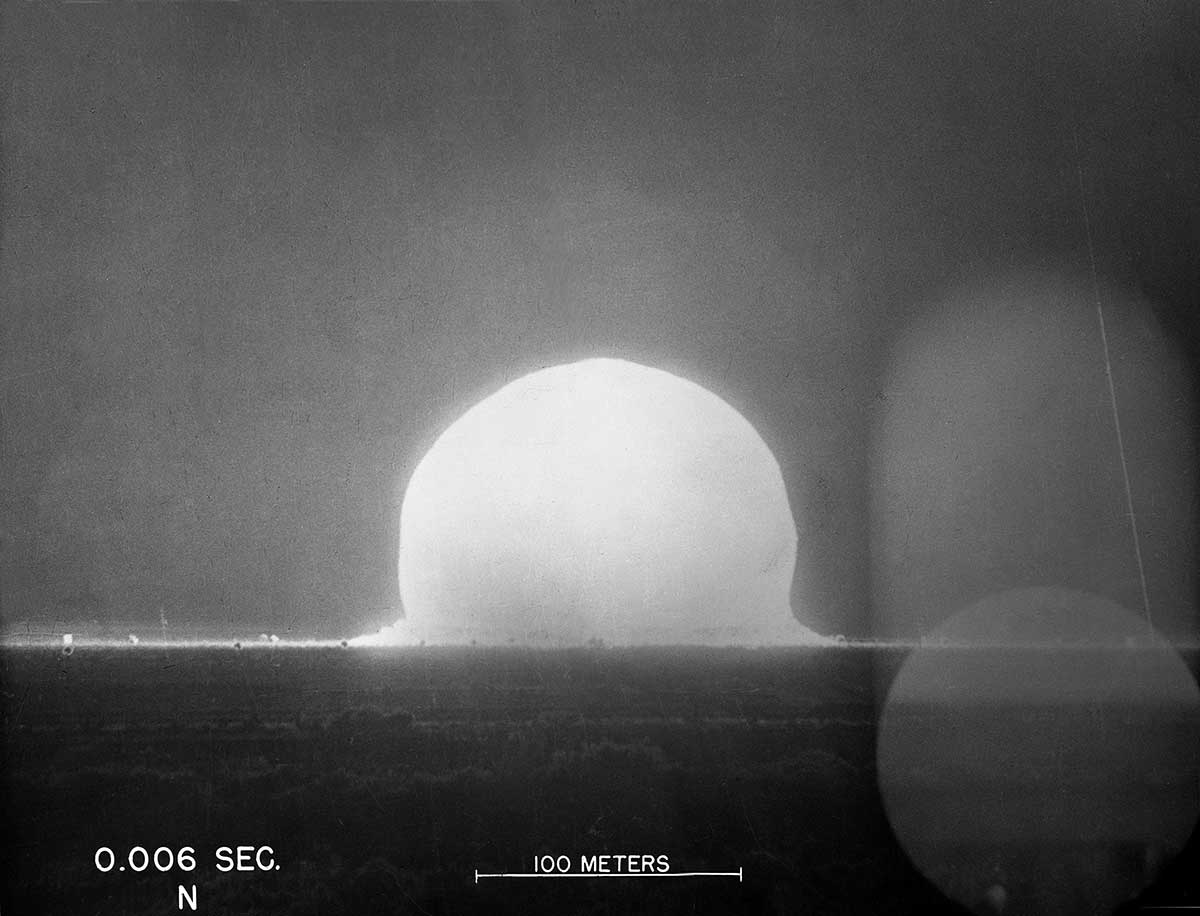

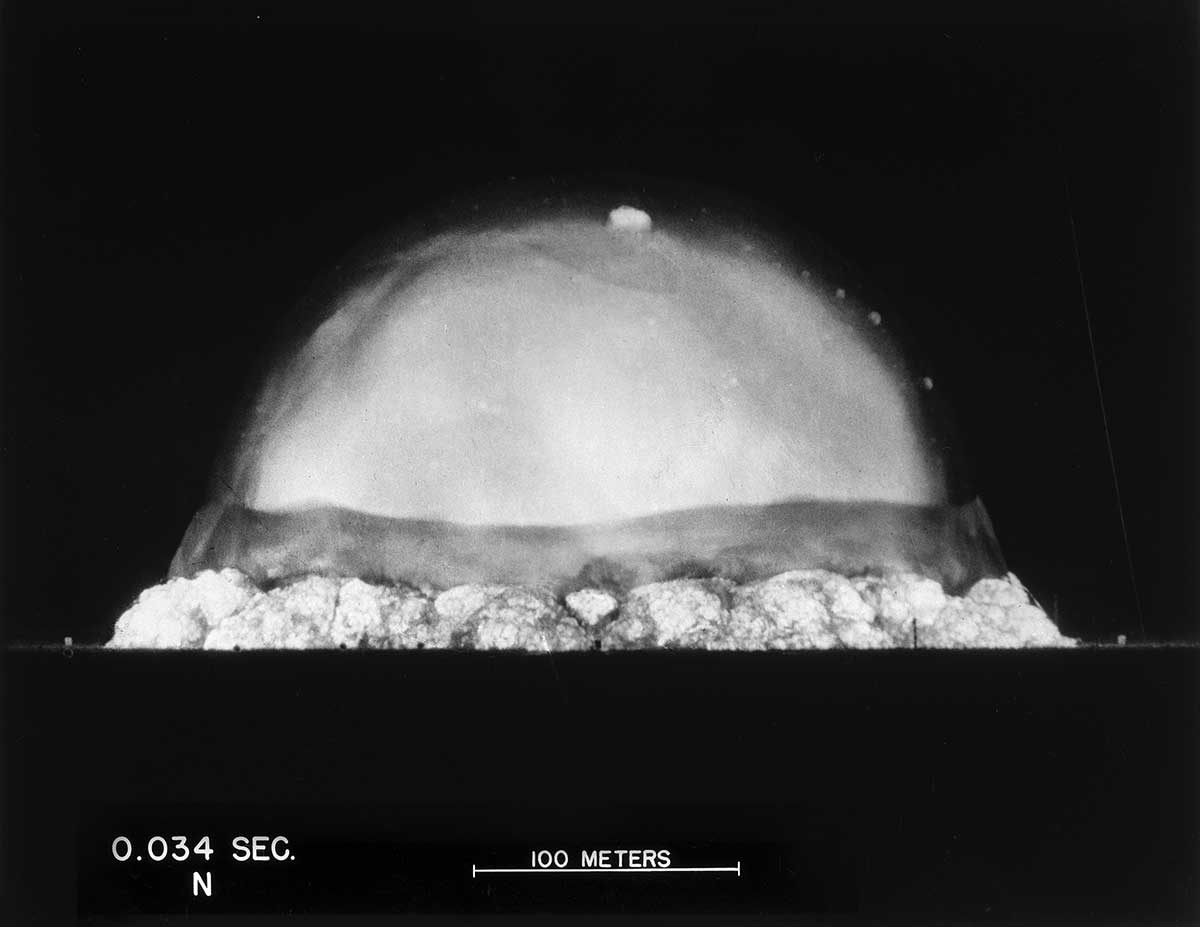

At that instant-5:29:45 a.m. Mountain War Time on July 16, 1945—came an incredible burst of light, bathing the surrounding mountains in an unearthly brilliance. Then came the shock wave that knocked over two men at S 10,000, then the thunderous roar. A vast multi-colored cloud surged and billowed upward. The steel tower that held the bomb vanished, the tower that held Jumbo, 800 feet away, lay crumpled and broken on the ground.

Wrote Enrico Fermi shortly after the test:

“My first impression of the explosion was the very intense flash of light, and a sensation of heat on the parts of my body that were exposed. Although I did not look directly towards the object, I had the impression that suddenly the countryside became brighter than in full daylight. I subsequently looked in the direction of the explosion through the dark glass and could see something that looked like a conglomeration of flames that promptly started rising. After a few seconds the rising flames lost their brightness and appeared as a huge pillar of smoke with an expanded head like a gigantic mushroom that rose rapidly beyond the clouds, probably to a height of the order of 30,000 feet. After reaching full height, the smoke stayed stationary for a while before the wind started dispersing it.” Fermi then went on to explain the simple experiment he took time to conduct that helped considerably in making the first early estimates of the bomb’s success.

“About 40 seconds after the explosion the air blast reached me. I tried to estimate its strength by dropping from about six feet small pieces of paper before, during and after the passage of the blast wave. Since, at the time, there was no wind, I could observe very distinctly and actually measure the displacement of the pieces of paper that were in the process of falling while the blast was passing. The shift was about two and a half meters, which at the time, I estimated to correspond to the blast that would be produced by ten thousand tons of TNT.”

Hans Bethe wrote that “it looked like a giant magnesium flare which kept on for what seemed a whole minute but was actually one or two seconds. The white ball grew and after a few seconds became clouded with dust whipped up by the explosion from the ground and rose and left behind a black trail of dust particles. The rise, though it seemed slow, took place at a velocity of 120 meters per second. After more than half a minute the flame died down and the ball, which had been a brilliant white became a dull purple. It continued to rise and spread at the same time, and finally broke through and rose above the clouds which were 15,000 feet above the ground. It could be distinguished from the clouds by its color and could be followed to a height of 40,000 feet above the ground.” Joe McKibben recalls that “we had a lot of flood lights on for taking movies of the control panel. When the bomb went off, the lights were drowned out by the big light coming in through the open door in the back.”

“After I threw my last switch I ran out to take a look and realized the shock wave hadn’t arrived yet. I ducked behind an earth mound. Even then I had the impression that this thing had gone really big. It was just terrific.”

“The shot was truly awe-inspiring,” Bradbury has said. “Most experiences in life can be comprehended by prior experiences but the atom bomb did not fit into any preconception possessed by anybody. The most startling feature was the intense light.”

Bainbridge has said that the light was the one place where theoretical calculations had been off by a big factor. “Much more light was produced than had been anticipated.”

A military man is reported to have exclaimed, “The long-hairs have let it get away from them!” While scientists were able to describe the technical aspects of the explosion, for others it was more difficult.

“Words are inadequate tools for acquainting those not present with the physical, mental and psychological effects. It had to be witnessed to be realized,” wrote General Farrell two days later. Nonetheless, many tried to describe the historic moment.

Farrell himself wrote:

“The effects could well be called unprecedented, magnificent, beautiful, stupendous, and terrifying. No man-made phenomenon of such tremendous power had ever occurred before. The lighting effects beggared description. The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun. It was golden, purple, violet, gray and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. Seconds after the explosion came,” first, the air blast pressing hard against the people, to be followed almost immediately by the strong, sustained awesome roar which warned of doomsday and made us feel we puny things were blasphemous to dare tamper with the forces heretofore reserved for the Almighty.”

William L. Laurence, whose sole job was to write down the moment for history, wrote:

“It was like the grand finale of a mighty symphony of the elements, fascinating and terrifying, uplifting and crushing, ominous, devastating, full of great promise and great foreboding.”

Another time he said, “On that moment hung eternity. Time stood still. Space contracted to a pinpoint. It was as though the earth had opened and the skies split. One felt as though he had been privileged to witness the Birth of the World-to be present at the moment of Creation when the Lord said: Let there be light.”

Oppenheimer, on the other hand, has said he was reminded of the ancient Hindu quotation:

“I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

At the time, however, probably few actually thought of the consequences of their work, beyond ending the war. Bradbury said recently, “For that first 15 seconds the sight was so incredible that the spectators could only gape at it in dumb amazement. I don’t believe at that moment anyone said to himself, ‘What have we done to civilization? Feelings of conscience may have come later.”

Bainbridge reports that his reactions were mixed. “When the bomb first went off I had the same feelings that anyone else would have who had worked for months to prepare this test, a feeling of exhilaration that the thing had actually worked. This was followed by another quick reaction, a sort of feeling of relief that I would not have to go to the bomb and find out why the thing didn’t work.” But later he told Oppenheimer, “Now we’re all sons of bitches.”

Ernest O. Lawrence is quoted as saying that from his vantage point on Compagna Hill, “the grand, indeed almost cataclysmic proportion of the explosion produced a kind of solemnity in everyone’s behavior immediately afterwards. There was a restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence as the event was commented upon. ”

At the control point, Farrell wrote, “The tension in the room let up and all started congratulating each other. All the pent-up emotions were released in those few minutes and all seemed to sense immediately that the explosion had far exceeded the most optimistic expectations and wildest hopes of the scientists. ”

Kistiakowsky, who had bet a month’s salary against $10 that the gadget would work, put his arms around the director’s shoulder and said, “Oppie, you owe me $10.”

Elsewhere the momentous event had not gone unnoticed. The flash of light was seen in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Silver City, Gallup and El Paso. Windows rattled in Silver City and Gallup. So intense was the light that a blind girl riding in an automobile near Albuquerque asked, “What was that?”

A rancher between Alamogordo and the test site was awakened suddenly. “I thought a plane had crashed in the yard. It was like somebody turned on a light bulb right in my face. ”

Another man, 30 miles away in Carrizozo, recalls, “It sure rocked the ground. You’d have thought it went off right in your back yard. ”

A sleepless patient in the Los Alamos hospital reported seeing a strange light. The wife, waiting on Sawyer’s Hill behind Los Alamos, saw it too, and wrote later:

“Then it came. The blinding light like no other light one had ever seen. The trees, illuminated, leaping out. The mountains flashing into life. Later, the long slow rumble. Something had happened, all right, for good or ill.”

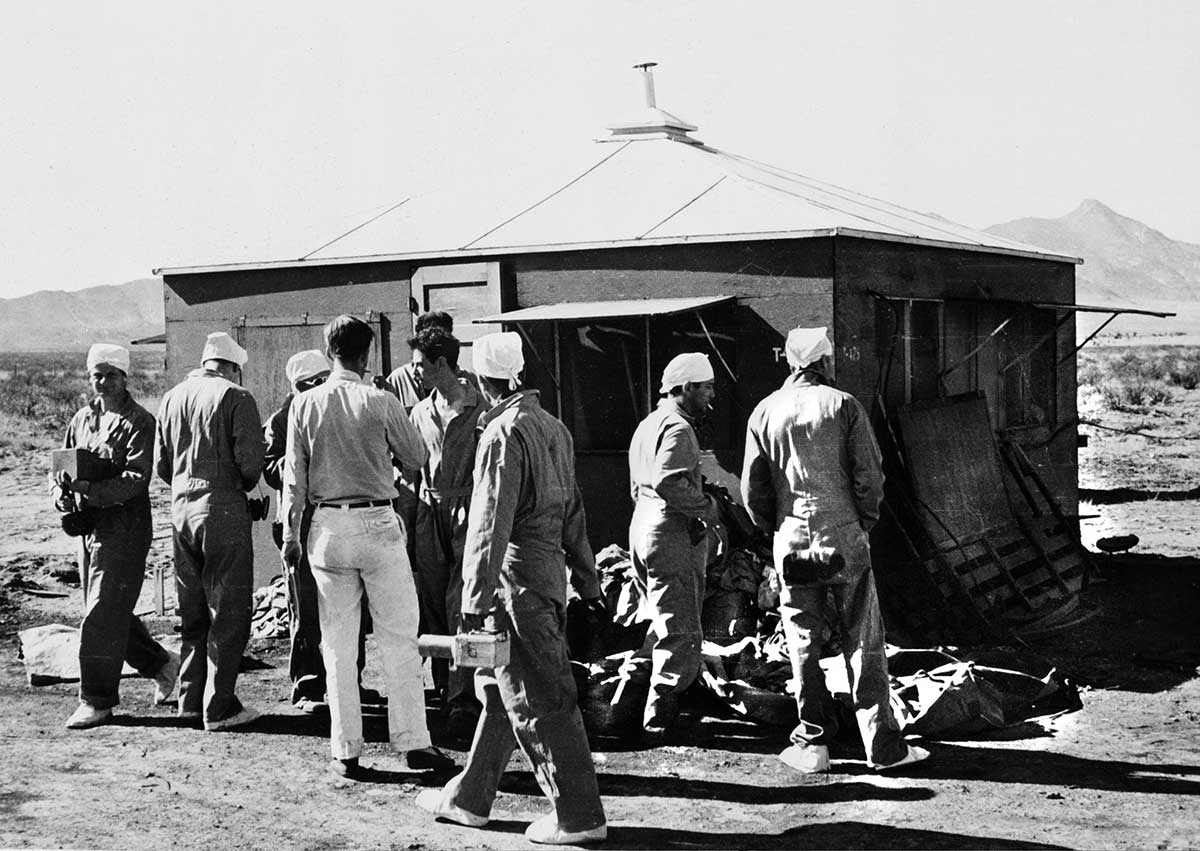

At the test site, as the spectators watched the huge cloud billow into the sky, the medical officers took over leadership of the three observation points, watching their counters and maintaining contact with Paul Aebersold’s crew of monitors patrolling the roads within the test site. An Entry Permission Group, consisting of Bainbridge, Dr. Hemplemann and Aebersold kept track of the reports and made decisions on movement of personnel around the site.

At first there was no sign of danger. Then suddenly, the instruments at N 10,000 began clicking rapidly showing that radioactivity was on the rise. Dr. Henry Barnett, in charge of the shelter, gave the order to evacuate and soon the trucks and cars were roaring past W 10,000 and on to Base Camp. It later proved to be a false alarm. Film badges worn by the personnel at the observation point indicated that no radioactivity had reached the shelter. Before long those without further duties were permitted to return to Base Camp and those with instruments in the forward areas moved in to pick them up.

As the sun came up, air currents were created which swept radioactivity trapped in the inversion layer into the valley. Geiger counters at S 10,000 began to go wild. The few men remaining there put on masks and watched anxiously as the radioactive air quickly moved away before the danger level was reached. Around 9:30 a.m. Bainbridge radioed the men in the slit trench at Mockingbird Gap to return to Base Camp.

Shortly afterward a lead-lined tank, driven by Sgt. Bill Smith and carrying Herbert Anderson and Enrico Fermi, moved in to Ground Zero to recover equipment and to study debris in hope of getting information on long range detection of atomic explosions. The tank was equipped with a trap door through which earth samples could be safely picked up in the crater.

Fermi later reported to his wife that he found “a depressed area 400 yards in radius glazed with green, glass-like substance where the sand had melted and solidified again. ”

Meanwhile, General Groves, who had planned to wait at Base Camp until all danger of fallout was passed, hoped to make good use of the hours by discussing with Los Alamos people a number of problems connected with the next job on the agenda, the bombing of Japan.

“These plans were utterly impracticable,” he wrote later, “for no one who had witnessed the test was in a frame of mind to discuss anything. The success was simply too great. It was not only that we had achieved success with the bomb; but that everyone—scientists, military officers and engineers— realized we had been personal participants and eyewitnesses to a major milestone in the world’s history.”

But Groves had other problems to keep him busy anyway.

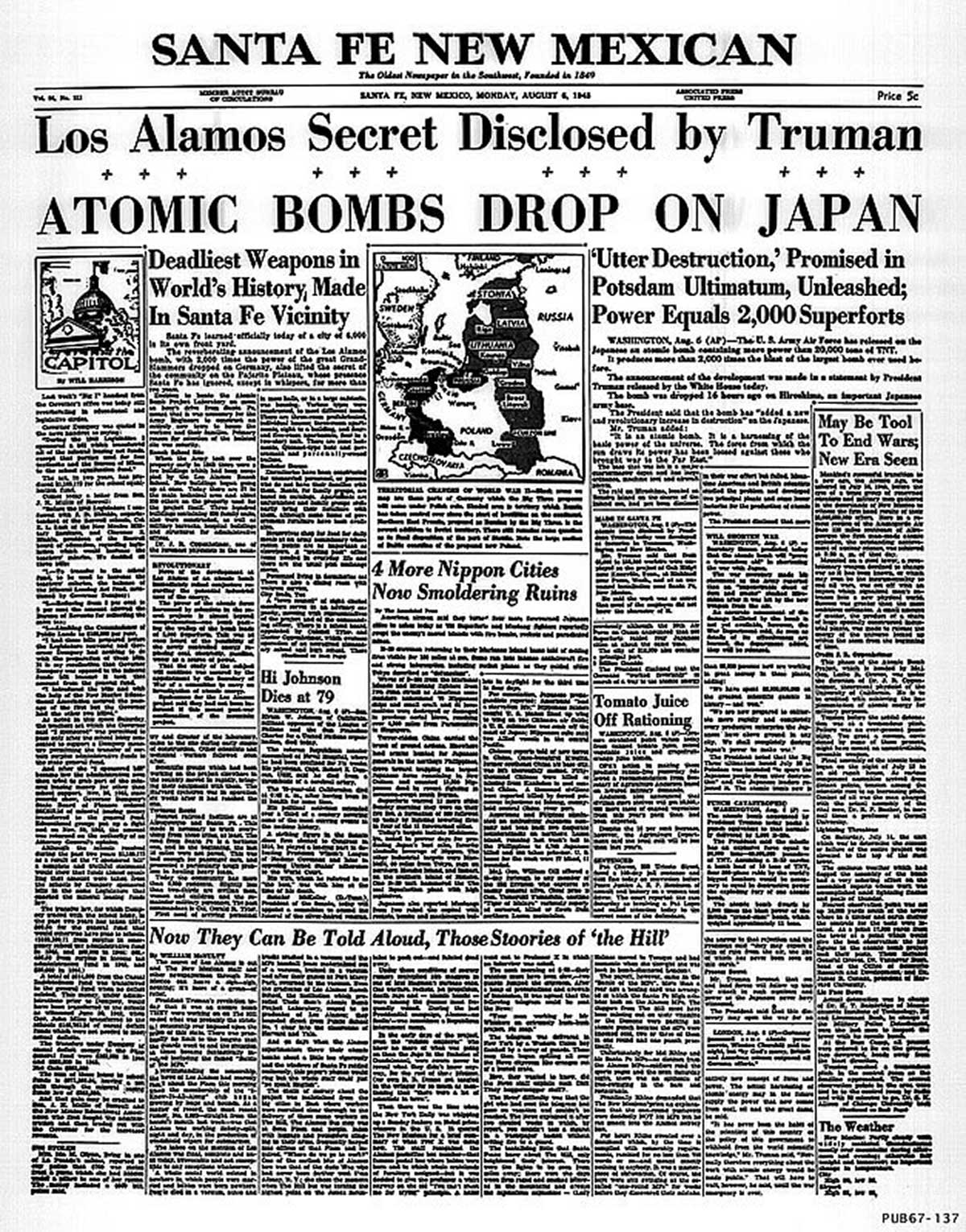

The explosion had generated considerable excitement around the state and as far away as El Paso. At Associated Press in Albuquerque, the queries coming in were becoming more difficult to handle. Intelligence Officer Lt. Phil Belcher, now the Laboratory’s Documents Division leader, was stationed at Albuquerque to keep any alarming dispatches about the explosion from going out. About 11 a.m. the AP man told Belcher he could no longer hold back the story. If nothing is put out now by the Army, he told him, AP’s own stories would have to go on the wire.

The Army was prepared for this kind of determination. Weeks before a special press release had been prepared and sent to the Alamogordo Bombing Range with Lt. W. A. Parish from Groves’ office. With it, Parish also carried a letter to the commanding officer, Col. William Eareckson, instructing him to follow Lt. Parish’s instructions, no questions asked.

About 11 Parish was instructed to make his release:

Alamogordo, July 16–The Commanding Officer of the Alamogordo Army Air Base made the following statement today:

“Several inquiries have been received concerning a heavy explosion which occurred on the Alamogordo Air Base reservation this morning. “A remotely located ammunition magazine containing a considerable amount of high explosives and pyrotechnics exploded.

“There was no loss of life or injury to anyone, and the property damage outside of the explosives magazine itself was negligible.

“Weather conditions affecting the content of gas shells exploded by the blast may make it desirable for the Army to evacuate temporarily a few civilians from their homes.”

The news ran in New Mexico papers and spread up and down the West Coast by radio. It didn’t fool everyone. Some days later, Groves reports, he was dismayed when a scientist from the Hanford project said to him: “By the way, General, everybody at DuPont sends their congratulations. ”

“What for?’ the general asked innocently.

“This is the first time we’ve ever heard of the Army’s storing high explosives, pyrotechnics and chemicals in one magazine,” he replied. Colonel Eareckson has since been nominated by sympathetic historians as one of the unsung heroes of World War II. Not only was he forced to take the blame for this gross mishandling of explosives, but he had to take his orders that day from a mere lieutenant.

By late afternoon it was clear there would be no difficulty with fallout. Bainbridge finally left the control center about 3 p.m. to return to the Base Camp for food and rest. General Groves, Conant and Bush left for Albuquerque to begin the trip back to Washington.

Groves’ secretary, Mrs. Nora O’Leary, who had been standing by in Washington since early morning for word of the test, received a coded message from her boss and at 7:30 p.m. sent the following message to Secretary of War Stimson at Potsdam:

“Operated on this morning. Diagnosis not yet complete but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations. Local press release necessary as interest extends a great distance. Dr. Groves pleased. He returns tomorrow. I will keep you posted.”

Although it would be weeks before the measurement could be correlated and interpreted it was immediately apparent that the implosion weapon was a technical success. The fire bail, Fermi’s calculations with bits of paper and other data available immediately indicated the yield had been greater than the most optimistic predictions. It was therefore possible for Groves to follow up his first message to Potsdam with another optimistic one the next day:

“Doctor has just returned most enthusiastic and confident that the little boy is as husky as his big brother. The light in his eyes discernible from here to Highhold and I could hear his screams from here to my farm.”

The message was clear. The power to crush Japan had taken on a new dimension. The device had worked beyond expectations, its flash seen for 250 miles, its thunder heard for 50, and Groves was sure the plutonium bomb was as potent as the uranium gun.

Through the day of JuIy 16, cars of weary, excited men headed back toward Los Alamos. There was still a great deal of work to be done and for those who were going overseas, the test had simply been a rehearsal.

A new Fat Man was scheduled to be delivered August 6.

When they stopped for meals in Belen the men talked of inconsequential things and listened to mystified citizens discussing the strange sort of thunder they had heard that morning and the way “the sun came up and went right back down again.” Occupants of one car did not recognize the occupants of the other. Security was as tight as ever. It was not until they reached the guarded gates of Los Alamos that the flood of talk burst loose.

Mrs. Fermi recalls the men returning late that evening. “They looked dried out, shrunken. They had baked in the roasting heat of the southern desert and they were dead tired. Enrico was so sleepy he went right to bed without a word. On the following morning all he had to say to the family was that for the first time in his life on coming back from Trinity he had felt it was not safe for him to drive. I heard no more about Trinity.” But during the day, rumors of the brilliant light so many had watched for and seen spread through the town. Although few people knew officially what had happened, most were able to sense or guess that the project to which each had contributed his part had been accomplished.

When he returned to the Hill that night, Fred Reines found the town jumping. One of the janitors Reines knew spotted the returning scientist, grinned proudly and said, “We did it, didn’t we?” “We sure did,” Reines told him.

At Potsdam, where President Truman and Prime Minister Churchill were waiting to meet with Stalin to discuss a demand for unconditional surrender from the Japanese, the news of the successful test of the Fat Man that morning bad a profound effect. Confidence in the test results and the reassurance that the first bomb could be ready for delivery on July 31 froze the previously tentative decision that the time had come to issue the surrender ultimatum. The atomic bomb had made invasion unnecessary and could provide the Japanese with an honorable excuse to surrender. The war could end quickly. There was no longer any need for help from Russia. Churchill and Truman approached the talks in extreme confidence.

There never had been much doubt that the guntype uranium weapon would work. By July 14, two days before the implosion weapon was tested, the major portion of the U-235 component began its journey overseas from Los Alamos. A few hours before dawn on July 16, just as observers in the Jornada del Muerto were witnessing the incredible birth of the atomic age, the uranium bomb was hoisted aboard the cruiser Indianapolis at San Francisco.

On July 26, the Indianapolis arrived at Tinian and two nights later transport planes arrived with the last necessary bit of U-235 and the uranium device was ready.

“The world’s second man-made nuclear explosion occurred over Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, three weeks after the Trinity test. On August 9, the third such explosion devastated the city of Nagasaki. Japan gave up the struggle five days later, and surrender ceremonies were held September 2.